To truly appreciate the significance of the Pride phenomenon in San Diego and all over the world, it is essential to understand the historical and social contexts from which it has emerged. Prior to the Stonewall Riots and the birth of the modern gay rights movement in the 1970s, LGBTQ+ people in San Diego had few resources. It was not a safe time to be out in the United States, period. Laws targeting homosexuality existed at the national, state, and local levels. Homophobia and hostility toward the community prevailed as mainstream attitudes. As a result, most LGBTQ+ people were not public about their sexual orientation or gender identity. However, an underground gay scene had been forming in San Diego for decades.

The city swelled with military presence during the wars that, coupled with the influx of millions of permanent tourists from the Panama-California Exposition of 1915-1916, resulted in a population surge. With such rapid growth, the LGBTQ+ community inevitably expanded and converged as well. Wartime meant new employment options at home and in service. Women experienced more financial independence, and everyone spent more time in same-sex environments.

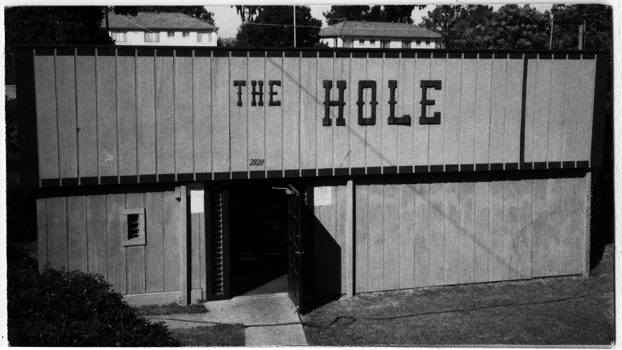

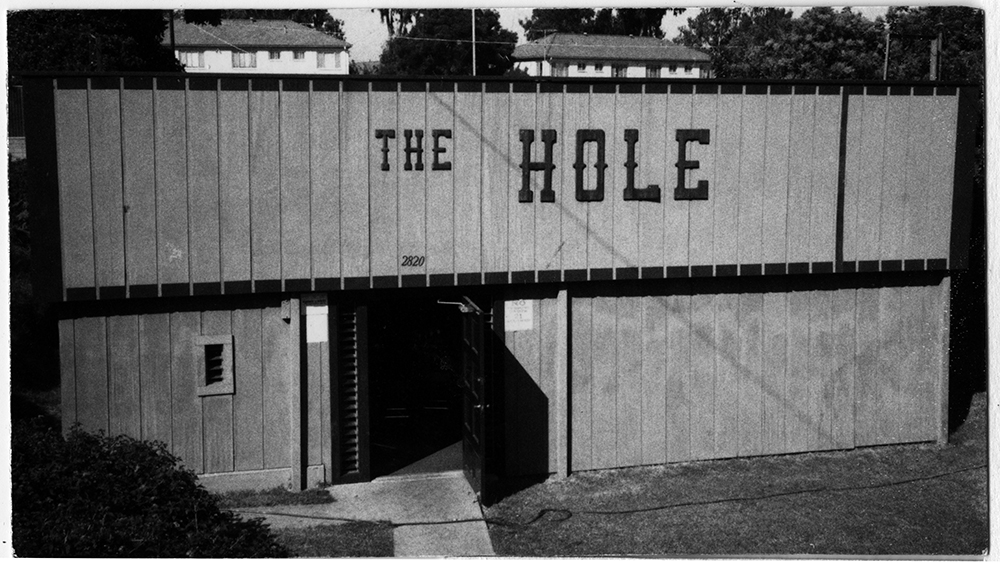

Gay social spaces began to emerge in private establishments such as boarding houses, bathhouses, theaters, and bars, as well as public parks and restrooms. The bars and clubs were a vital fixture of American gay life during the first half of the 20th century. Some of the earliest gay bars in San Diego include The Brass Rail and Bradley’s downtown, Cinnabar in the Gaslamp Quarter, The Hole in Loma Portal, and The Gizmo in Hillcrest. Servicemen patronized the downtown bars, which often functioned as straight-by-day, gay-by-night establishments. These spaces served as the primary locales for LGBTQ+ people to socialize for decades. Due to the criminality and stigma of homosexuality, however, privacy and anonymity were a top concern for many. As a result, gay bars and clubs were typically dark, understated venues where people weren’t willing to share much information about themselves for fear of exposure.

Nonetheless, the bars and clubs functioned as a refuge from closeted life, and as a place to meet other LGBTQ+ individuals. Longtime San Diegan Jeri Dilno experienced the city’s gay scene as a young lesbian in the 1950s and 1960s. She recalls that gay and lesbian people during this period adopted a kind of “double-life” that was compartmentalized into publicly straight and privately gay identities. The bars, she says, were “pretty depressing [but] an escape from the constructed outside life.” Peggy Heathers, who moved to San Diego in the mid-1950s, remembers a similar experience while noting that much fun was had as well. For San Diego lesbians, dancing became commonplace in the 1960s, especially at the Barbaree in Mission Beach. Dancing between men, on the other hand, was viewed more critically and seldom occurred before the 1970s.

Men were able to meet in a variety of settings. The Armed Forces YMCA in downtown San Diego was a well-known boarding house for servicemen to cruise (that is, seek out a partner for a sexual encounter). Old Plaza Park, Presidio Park, Black’s Beach, and Marston Point (“the Fruit Loop”) were also popular outdoor grounds. A continuous flow of newcomers into San Diego over the decades led to insufficient living accommodations, which necessitated shared housing among servicemen. This practice enabled men seeking men to interact more freely. Bathhouses were a San Diego tradition dating back to the mid-19th century. They evolved from establishments where gay men would cruise covertly amongst straight men into explicitly gay establishments. The Guild Theater, which showed soft core pornography, also enabled discreet sexual encounters.

There isn’t a clear record of spaces exclusive to gender non-conforming and trans folk in San Diego. Most likely, certain bars catered to a mixed crowd of drag queens, trans, and gay people. But discrimination against drag queens and trans people within the gay scene prompted fissures in the community and likely impacted the spaces “all” were welcome in. The earliest known drag venue in San Diego is the Show Biz Supper Club, which opened in 1968. Prominent community figure Nicole Murray-Ramirez relocated to San Diego as a preoperative transsexual in the late 1960s and found it a difficult place to be gay compared to Los Angeles or San Francisco. Despite the popularity of trans prostitutes among servicemen downtown, Murray-Ramirez experienced extreme discrimination as a transsexual. Cruelty and violence towards trans bodies was inflicted by society at large, the police, and the gay community. Drag queens and trans folk were viewed as “freaks […] at the bottom of the totem pole,” Murray-Ramirez explains.

Of course, gays suffered at the hands of police as well. Bars and cruising areas were subject to regular harassment and raids. Prominent San Diego gay activist Jess Jessop (1939-1990) recalled that police cars would park across the street from gay bars and shine a spotlight on the door for hours at a time. Officers would also lurk in the bushes at the Fruit Loop, waiting to arrest unknowing cruisers. Drag queens had to enter and leave performance venues in plainclothes, and ensure a wig or high heel was not peeking out of their bag. Sometimes, newspapers would even print the personal information of people detained or arrested in the raids, which outed many and threatened their safety. Such practices were backed by laws prohibiting sodomy, “lewd conduct,” and cross-dressing. This harassment by law enforcement and the media continued well into the 1970s. Nevertheless, LGBTQ+ people maintained their social spaces in San Diego discreetly for nearly a century.

Activism before Pride existed in the form of publications and support networks. It is rumored that a San Diego chapter of the Mattachine Society existed in the 1950s, although no documentation confirms this. The Ladder, a newsletter published by the lesbian civil rights group Daughters of Bilitis made its way to San Diego in the 1950s. A “secret society” for gays called the Sons and Daughters of Society met during the 1960s, maybe earlier. In early 1969, Bill Gautier, a drag queen known as Glenda, created Gays United for Liberty and Freedom (GULF) and ran a help hotline from his home on 30th St. GULF provided information on gay-friendly doctors, lawyers, and other professionals, as well as locales for cruising, bars, and social activities. Around the same time, Father Patrick X. Nidorf formed Dignity, a support group for gay catholics in San Diego that later moved to Los Angeles.